Journeys and Resting Places

- Foreword

- Part I: Growing Up in Northern England

- Part II: Soldiering On in Southern India

Copyright © 2012. All rights reserved.

The moral rights of the author and editors have been asserted.

Copyright © 2012. All rights reserved.

The moral rights of the author and editors have been asserted.

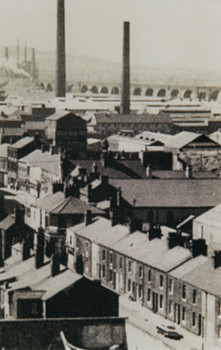

I was born at No.41 Witt Road, Widnes, and according to my Mother, weighed 10 and a half pounds at birth. (I am unable to confirm this statement.) My Grandmother registered the birth. I cannot imagine how so many people lived in this small house at this time as my Father had five brothers of whom he was the oldest. Witt Road was one of the many streets of terraced houses built in the 19th Century to house the influx of workers needed for the growing chemical industry. The houses were of basic construction and usually had two rooms downstairs and two upstairs, together with a small kitchen at the rear and an outside lavatory in a small, tiled, back yard. There could also be a wash-house built on to the end of the kitchen.

The houses were rented, often on a short term basis, from the Landlord who owned them. My Grandad and Grandma Adams lived in such a house in Witt Road and my parents must have been living with them since their marriage in 1919, after my Father was released from the Army, or “disembodied” as his discharge papers declared. At this time he was employed as a “Sampler” in a chemical works laboratory although on his marriage certificate of the previous year his profession was given as “Platiniser”.

Before the War he had worked at the Golding Davies Works of the United Alkali Company and is shown on a photograph of workers taken in 1906 when he was 14 years old. The Golding Davies and Mathieson Works were amalgamated as Marsh Works in 1915 and after the War he worked there for the remainder of his life, except for a short period towards the end of 1929, when he spent some time at the Ardeer works of Nobel Division (I.C.I. Explosives). In the more skilled occupation of “Platiniser” he had been given a period of temporary release from the Army in August 1916 until he was recalled in April 1918 with the rank of Sergeant. (Before 1914, the Lead Chamber process was still the only method of sulphuric acid production in this country, but on the outbreak of war there was a sudden increased demand for strong acid for the manufacture of explosives. This demand could only be met by the improved Contact Process for acid manufacture and this required a suitable catalyst, the best one being platinised asbestos. This development had clearly led to a desperate need for skilled platinisers). However, he was subsequently recalled to the Army in April 1918 and given the rank of Sergeant, which he held until his discharge in 1919. One of my Father’s stories that I recall concerned a tin of sausages that he had brought back from France during the War for his Mother. She had heated this incautiously in a pan causing an explosion that plastered sausage over the kitchen ceiling!

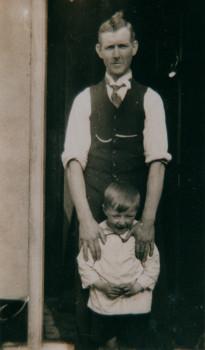

When I was 16 months old we must still have been living in Witt Road as there is a photograph of me wearing a lacy frock, and others where I was wearing some kind of overalls, taken in the backyard of this house. My Father had bought a Vest-Pocket Kodak camera and I suppose these were his first photographs. It was said that at this time I had shown some physical aggression towards a neighbouring boy, Freddie Whitfield, but I have no recollection of this incident in which a hammer was said to have been used, but it was related to me by my parents in later years.

Around about 1920, Widnes Corporation started to build houses for the growing population after the War; one of these developments was the Fairfield Housing Estate that was built on fields lying between Victoria Park and Peelhouse Lane. The road on the east side of the Park and the west side of the housing estate was called Fairfield Road and it was to No.92 Fairfield Road that my parents and I moved into a newly built Council House. This must have been by May 1922 as an old photograph shows me there, sitting on a wooden horse that I can still remember. It was made by my Grandfather Hinde, whose hobby was carpentry, and was covered with a skin of Army khaki uniform cloth and sported a fine horsehair tail. I also was wearing a natty sailor-suit at this time, having presumably grown out of the frocks I had previously been dressed in. It is significant to record that my Grandma and Grandad Adams had also moved at this time from Witt Road and rented a similar house in Belvoir Road, always referred to by us as “Bell - Voyer Road”, and only a short walk from our Fairfield Road house so we often visited each other in later years.

The Fairfield Estate had streets named after trees: Sycamore, Lilac, Elm, Chestnut, Larch, Cedar, and Cypress Avenues, and this practice was continued to the north in the Lockett Road estate with Acacia and Alder Avenues. The houses varied in style, some being in blocks of four with a central passageway to the back, and others being semi-detached. Our new house, No.92 Fairfield Road was a semi-detached building with a lawn at the front and a large back garden which my parents must have had to break-in from the field on which the house was built. I remember that Father would unearth pieces of wood and builder's debris, and when holes were dug years later it was often possible to see the remains of decayed turf which had been buried when the ground was first dug.

Most of the houses were left as plain brick but ours together with the two adjacent ones to the north were rendered and painted cream with a wide black band along the bottom. These three pairs of houses were set back more from the road than the brick ones so we had larger front gardens with square lawns. The ground floor windows at the front had louvered wooden shutters, painted green, and fastened back to the wall with S-shaped catches. I don't recall them ever being used to cover the windows and they were regarded as ornamental. The front door opened into a small hall with a flight of stairs to the bedrooms. Underneath the stairs was an empty space, which I used for “camping-out” games, using an old blanket to cover the cold lino floor. On the right of the hall was the bathroom and a separate lavatory. The bathroom was unheated except for a gas geyser to heat the water for the bath. On the left of the hall was the living room which had a fireplace and some wooden shelves built in the alcove to its left. This room occupied the full width of the house with a sash window at each end; a door led into the kitchen with its sink, gas cooker, boiler and mangle. There was a small pantry, and a coal-shed only accessible from outside the house. Going upstairs, my parents' bedroom extended across the full width of the house and a small landing at the top of the stairs led to “our” bedroom (for my younger brother Norman and me) at the front and to a third small bedroom always known as the “Lumber-room” and full of oddments and domestic clutter.

The house was lit by gas with wall lights and it wasn't until 1931 that the Council Houses were wired for electricity. The gas jets, lit with a match or paper spills from the fire, heated an inverted incandescent mantle giving out a characteristic greenish-yellow light. The mantles consisted of a knitted or woven cotton or ramie fabric in the shape of a small cup supported on a ceramic ring which held it over the gas jet. The fabric was impregnated with a compound containing thorium and cerium oxides and when new could be easily handled. However, after burning off the fabric base on first use, the oxide skeleton was very fragile and couldn't be touched without breaking.

Father had some basic wood-working tools and I think he made the side-gate to protect the back of the house as no other houses had this feature. This gate and the fence, together with the ornamental shutters on the frontage, were still there in 1976 when I last saw the house. He must have also made other things for the garden as we had a cold frame, bench seat, and in later years, a dog kennel. I remember him making a rather clumsy folding screen in wood, with plywood panels from tea chests held in by beading. This screen was a lot of trouble to make as the plywood panels were held in by lengths of beading which split readily when nailed to the frame with oval nails which were hard to keep from bending. The whole screen was then stained brown with Potassium Permanganate.

The back garden was partly dug and cultivated for vegetables but there were some rough patches. It was enclosed by privet hedges as were the neighbouring gardens, and these needed to be cut several times a year with the cuttings burned in a smelly bonfire. In the garden was a large, old, wooden wheelbarrow, which, when turned upside down served as a ship, motor-car or railway engine on which to play, the cast-iron wheel being turned by hand as a “steering wheel” or “engine” as the game required. We were very imaginative. The one who played the part of the “driver” in these games was always called “Bill” for some unknown reason. The front garden was mostly grass with a few stone-bordered flower beds and the inevitable privet hedges. For neighbours, we had some families with children of similar age who I often played with, usually out-of-doors, either in our garden or in the neighbouring park across the road where there was a convenient gate.

I was brought up in the shadow of the Great War and I am sure that its horrors still lingered in the minds of Father and Mother. Naturally, some of the games I played with my young friends involved fighting and trench-warfare, and we dug shallow trenches and “shell-holes” in the back garden at times. We found that a clod of our dry, clayey-soil thrown on a hard surface would burst giving a satisfying shower of fragments, but I got into trouble once when I threw one through a pane of glass in the living room window. Father still had his wartime steel helmet which I wore sometimes. At an earlier age, I got into more trouble when I buried Mother's wrist watch in a tin box somewhere in the garden as “buried treasure”, and it was not recovered for some days, by which time it had suffered badly from damp.

Fairfield Road was on a bus route and Corporation buses would pass our house en route to Farnworth Street. Even so, there was very little traffic and we often played in the road without troubling anybody. Sometimes I had the job of collecting any horse manure that appeared in the vicinity of our house, and this went on the back garden as fertiliser. In hot summer weather the road would develop “tar” bubbles at the edges and these were played with. If you took care to moisten your fingers with spit, the pieces of “tar” could be moulded into balls or drawn out into various shapes. We usually ended with tarry hands (if not clothing - engendering more trouble!) and had to clean up using butter and rags. Another favourite game was climbing on our side gate; I don't recall ever being discouraged by my parents on any spurious health and safety grounds. With the gate bolted it was like being in a fort and we had games of “Cowboys and Indians”, sallying out to catch prisoners who we tied up in a gentle manner to a garden clothes post, whether boys or girls.

In those days the streets were lit by gas lamps, each lamp-post having a side arm at the top to serve as a support for a ladder when the glass had to be cleaned or other maintenance carried out. A rope thrown over this arm made a convenient swing. Every evening, the lamp-lighter would make his rounds, passing our house on the way. He carried a long pole with a burning oil-lamp at the top as well as a hook with which he turned on the gas and lit the mantle. In the morning he went round again to turn off the gas to each lamp. After I started school, a small group of us would play around a gas lamp in Lockett Road during the evening, this being the only place where we could see what we were doing.

Whenever there were any road-works there was always a night-watchman with a little shelter to sit in like a sentry-box, and he always had a coke brazier to keep himself warm and cook food or make tea. If we were lucky enough to have a watchman in our area we always used to enjoy a warm at his brazier on a cold night and a chat with the man. Often there was a steam-roller to look after and these were very interesting to us. They had a brass badge of a rampaging horse on the front with the motto “Invicta”. I remember when electricity came to our road there was also a night-watchman to safeguard the equipment and cable but by this time I had moved on to other interests.

Some of the furnishings of our living room at No.92. Fairfield Road stick in my mind. We had a mahogany table with two folding leaves standing on a square base with four ball and claw feet. There was a drawer at one end where oddments were kept. It is interesting to note that this table was the most valuable piece of the family furniture when it was all later sold, in spite of the fact that the surface at one end of table was somewhat marked by small holes, the accidental result of my efforts in drilling small rigging blocks for a sailing-ship model I made in the 1930's. There was also a sofa with its head at the left end. It was stuffed with horse hair, and somewhat uncomfortable to bare legs owing to the odd stiff hairs that protruded from the covering material. These long hairs could be pulled out with the fingers at times. The only other item that I recall was a stand for the “wireless”. I think that this must have been made by Grandad Hinde as it was in stained and varnished pine after his style of work. It stood about a yard high and below the top on which the “wireless” stood, was a cupboard to hold batteries. It stood in a back corner of the room near the window, so that the aerial and earth wires could be led in conveniently. At a later date we bought new furniture and I remember us all gathered in the living room when we had a visit from a Widnes dealer, Barney Dutton, who made an offer for the old things as well as the kitchen mangle which was then replaced by a wringer. At the time, I felt very sad to see our old familiar furniture go for a knock-down price.

Although we had a bathroom with a gas geyser to heat water, the room was unheated, and as a very small boy I was bathed in a galvanized bath-tub in front of the living room fire. This was about the only time that I saw myself completely bare and I remember vividly, that on these occasions, I felt very fragile and vulnerable for I was rather thin and skinny at this age. The fire in the living room made this the only warm room in the house in cold weather.

Mother did the washing in the kitchen using a dolly-peg and tub before putting the clothes through the stout wooden rollers of a heavy mangle turned by hand. I would sometimes help to turn the mangle but it was hard work for a small boy. This mangle was later replaced by a small wringer with rubber rollers making the operation easier. She did the ironing using a flat iron heated on the gas stove as there was no fire in the kitchen. This meant that she had to hold the iron in a cloth pad and test its temperature on a piece of white cloth before use, consequently there was always a smell of singeing on wash days.

In the process of ironing, she rested the hot iron on a steel shell-base standing on the table. This must have been a war souvenir. It was a heavy steel casting about three inches in diameter and two inches high with sides half an inch or more thick. A wide copper “driving-band” encircled the outside making quite a decorative feature. In practice, when a shell is fired from a gun, the softer copper of the “driving-band” is forced into the spiral rifling of the gun barrel thus imparting a spinning motion to the shell which results in a more accurate line of flight than if the gun barrel had been smooth. The top of this shell base had been cut off squarely and the edge rounded. There was also an oil lamp made from a flattened, round, steel bulb into which was screwed a solid brass wick holder. I never saw or heard of this lamp ever being used but I often used to play with it and the shell base.

Mother had a number of sayings that she would come out with at appropriate times. If anyone asked her how much a thing cost, she would reply “Money and Fair Words”. If we pestered her about what we were going to have for our next meal, she would say:- “Three jumps at the cupboard door and a slide down”, and if we were asking what she had in some box or drawer, she would say:- “Nothing for meddlers and crutches for lame ducks”, and that would be all we were told.

At one time, she went through a phase of rug-making and we all got involved in producing a hearth-rug, cutting the lengths of wool and laboriously knotting them on the canvas. She chose the colours and designed the pattern herself. It was in the form of a rising sun with radiating rays and turned out very well, the rug being completed by stitching on a backing of hessian. We also had small rugs of black wool which she had made to place by some of the doors. For rougher use, for example in kitchens, rag rugs were used as they were hard wearing, but they were usually dingy and unattractive. They were made very cheaply by fastening strips of old woollen cloth, about 4” x 1”, to hessian obtained from old sacks; Grandma Adams always had a rag rug before the living room fireplace in her house in Belvoir Road. Over the back of the living room settee we had a long anti-macassar, presumably one of the Hinde souvenirs from Egypt, as it had a procession of Egyptian gods and goddesses in applique work along it. I would think that the colours had originally been bright but I remember it as rather faded. We had it for many years.

Mother would often sing while working around the house, her repertoire consisting of popular songs of the war years, music-hall songs and hymns. I can remember some of her favourites although I can only give the opening lines that stick in my mind: “If you were the only girl in the world”, “Among my souvenirs”, “When I leave the world behind”, “Roses are blooming in Picardy”, “If those lips could only speak”, “I stand in a land of roses” and a hymn to the tune “All through the Night” (this was a particular favourite). I can picture her now, answering a knock at the front door, singing or humming to herself and taking off the “pinny” she habitually wore while working in the house. It was not done to answer the door wearing a “pinny”!

Father had a party trick which he would show us. It involved balancing a plate on the palm of his hand and passing it under his arm in a smooth movement and finally arriving back at the starting position. He always said it was more effective with a jelly on the plate. He also had a nonsense puzzle which we heard many times: “If it takes a yard and a half of tripe to make an elephant a sleeveless waistcoat, and it takes a blind rat two days to crawl through a barrel of gas-tar, then how long is a piece of string?”. He had a best pair of leather gloves, lined with reindeer fur. The rather coarse hairs on the fur were arranged to point inwards so that the gloves went on easier than they came off. I liked to try them on and experience this effect when Father brought them out to wear. He would say “I chased that reindeer for miles!”.

He had a number of stories about men in the Works or people at Widnes market, some rather apocryphal, such as a story about a rather dirty and disreputable man called “Old Sequaw”, who was reputed never to take off his clothes. When he was taken ill and had to go into hospital his clothes were removed but as the surgeon started to operate the patient was found to be still wearing a vest! There was also a Tooth-puller who operated at Widnes market on a Saturday night. Apparently the extraction of teeth was carried out in public before an interested crowd of spectators, the groans of the victim being drowned out by an assistant who beat a big drum.

If groceries were wanted during the day, Mother would send me to the Co-op shop in Derby Road near the bottom of Farnworth Street. There was a long counter on either side of the shop, one side dealing with “dry” goods and the other with dairy products and bacon, and I was always interested in the way the assistants would cut me slices from large sides of bacon on a hand-driven machine, or weigh out and pat into shape butter from a big block using wooden butter pats. I had to follow Mother's instructions to the letter, asking for the exact groceries she wanted in detail or I would get sent back. The assistants would try to take advantage of, or tease, a small boy and I had to check my change carefully.

When we went down to Widnes on a Saturday afternoon, Mother and I would walk from home, going down Deacon Road, Albert Road and Widnes Road to the Market near the Town Hall, calling at various shops on the way. We did most of our shopping at the market and, when heavy laden, came home by bus from the bus stop outside St.Paul's Church. In Albert Road we would call at the Maypole dairy where the assistants were even more adept at the use of butter pats than at the Derby Road Co-Op. On the opposite side of the road was Woolworths where everything was priced at sixpence or less, and further along on the same side of the road was Piper's Penny Bazaar selling lots of small domestic items from long display counters overlooked by the shop assistants. At the Market, we often patronised “The Jew”, an obliging man who sold a wide range of household articles from pins and needles to toiletries and hair creams. Mother was well known at some stalls and would chatter with the owners while examining their fruit and vegetables. She considered herself an expert in such matters as she had worked in a greengrocers at Aintree in her younger days. The larger, open market at Widnes was roofed over and on gloomy afternoons and at night the market stalls were lit by paraffin flares which were hung over them. The closed market was in a brick building and had better-class stalls selling fish and meat and more delicate goods. In the open market it was always interesting to watch the crockery salesmen as they usually had an upturned, empty tea chest on which they thumped the items of crockery to show that there were no flaws in them.

On Bonfire Nights, we would have a fire of fairly dry material in our back garden, having scoured the neighbourhood for bits broken off trees and scrap wood. We would have some fireworks, bangers and rip-raps being general favourites as they were the cheapest and noisiest, while my friend Don Machin would come along with one or two more expensive fireworks which we would all enjoy. When the fire had burned down, we would roast potatoes in the red hot embers and it was great fun to get them out with their skins smouldering, and a few burnt fingers. I always enjoyed the taste of steaming hot, half-burned potatoes with their charred skins.

At Christmas, we had the normal ritual of presents in stockings, tied to the foot of the bed, always with nuts or a tangerine in the toe. At tea-time on Christmas Day we had an old artificial Christmas tree and this was set in the centre of the tea-table. The tree carried a few glass baubles and on the ends of its branches were small metal holders to support wax candles, some 3 or 4 inches long. These were lit at tea-time and we would eat our tea by candle light. This process was repeated on Boxing Day to use up the remaining halves of the candles, after this, the tree was folded up and put away for next year.

Together with a few friends I would go round the estate carol-singing towards Christmas in the hope of earning a few pennies. We were very rarely successful. After singing at one house in Lilac Avenue for some time, a man came to the door, stood there silently until we were getting embarrassed, and then just asked us if we had seen a paper boy on his rounds. (The paper boys went round in the evening selling the Liverpool Echo). He didn't give us anything for all our singing. We always called at our house and Father would come out and give us some “hot” pennies that he had been warming on the hearth especially for us. Hunting for the dropped pennies was about the most interesting thing that happened to us on these outings!

Birthday parties were decidedly uncommon events with us in Fairfield Road but on at least one of my birthdays I recall inviting a few friends to tea in the afternoon. We didn't have any organised party games but after tea were left to our own devices, and played in the garden. It could have been on this occasion that I managed to break the pane of glass in the living-room window as I have already mentioned. On one memorable occasion, I was invited to a proper birthday party given by Ernest Swift who lived in one of the council houses on the south side of Lilac Avenue. His father ran a haulage business and they were better off than we were. This was my first experience of a properly organised birthday party and I enjoyed it. Among the games we played were “Spin the Trencher” and “Postman's Knock” and I found these games embarrassing, for, as well as boys at the party who were strangers to me, there were also some girls who, in my opinion, put a damper on our fun. I once invited Ronnie Owen to come to a birthday tea, and we called at his home on the way back from school to ask for permission from the two aunts he lived with. They somehow got the impression that it was to be a birthday party and when he told them later that he had only had tea with us, they were cross and tried to stop him playing with me.

We had a medicine cabinet which stood on a chest of drawers in our bedroom. This had probably been made by Grandad Hinde and was of stained and varnished softwood. It had double doors and a central shelf and contained a number of medical oddments such as tincture of iodine, zinc oxide powder, Iodex, glycerine, etc., but there were also some bottles of patent medicine and food supplements. These included bottles of Parrish's Chemical Food (a wine-coloured liquid, rich in iron), Angier's Emulsion (a creamy liquid containing cod-liver oil), Raspberry Syrup and Olive Oil (this separated into two layers and had to be well shaken to mix it up), and Cod-liver Oil and Malt (a thick, brown, viscous liquid - not unpleasant to the taste). Sometimes, when I was at a loose end, I would sample some of these concoctions, taking a tea-spoonful of each in turn. I never suffered any ill effects so I imagine that they were all rather bland medicaments!

During the 1920's we used to get a number of street traders coming around the housing estate. One of our regulars was the “Pop” man from St.Helens, who came weekly in the summer months with an open lorry stacked with gallon, earthenware jars of “pop” - ginger beer, dandelion and burdock and others, all very gassy. He collected the empty jar from the previous week when we bought our fresh supply. He was a “pop-ular” visitor! Once, Father made some ginger beer and stored the bottled product in the bathroom under the bath. Over several days bottles exploded as fermentation had not finished when he bottled his brew. The Walls ice-cream man would come round on his tricycle and cold box labelled “Stop me and buy one!”. One of his popular items was “Snofrute”, a triangular prism of frozen, coloured water, rather like the present day ice-lolly except that it was sold in an open-ended, three-sided, cardboard tube which had to be peeled back so that the ice could be sucked at one end. Melted ice usually ran down your arm from the other open end.There were other ice-cream carts, some pushed by hand and those of Gandolfo's, which were motorised. They carried a large churn of ice-cream to be sold as cornets and wafers. When war broke out in the late 1930's, Gandolfo's vans carried a large notice declaring “Naturalised since 1907” or some such date. This was to counter any anti-Italian feeling.

Another common visitor was a rag and bone man with his trade call which sounded like “Ragbone!”. Some of these men pushed a handcart while others had a horse and small cart on which they would ride. They were in search of old clothing, especially woollens, for which they would give blocks of an abrasive composition known as “Donkey Stones”. These were used for coarse scouring, in particular, on stone doorsteps and floors. The housewives living in the rows of terrace houses in Widnes took a pride in scrubbing their street doorsteps every day. Now and again we would see a knife and scissors grinder looking for customers. He would have a special kind of wheelbarrow in a wooden frame which transformed into a treadle-operated grindstone which he would use to sharpen kitchen knives and tools. These traders were more often seen in Farnworth Street and the more built-up parts of the town. In some of the streets in West Bank however, the custom was to sharpen the carving knives on the sandstone window sill by the front door of the house, and the wear produced by this activity could be seen on many house fronts before the houses were demolished long after the War.

Our milk was delivered each day by a milkman with a horse and trap which carried milk churns. A churn was carried to the front door and the milk was measured into Mother's jug using pint and gill measures hanging from hooks inside the churn. Our usual milkman was Irish and always wore a sprig of shamrock on St. Patrick's Day; Mother would beg a piece from him every year and put it in a glass in the living room. After my brother Norman was born, this shamrock acquired even more significance.

1927 was a significant year for two reasons. Firstly, I got a new brother, and secondly, I was very ill and had to go to hospital for the first time in my life. When I got up one Thursday morning, I was surprised to find Grandma Adams in the house and was informed that I had a new baby brother, Norman. I was very puzzled by this but also quite pleased although I realised he would not become a playmate for several years. It was suggested to me that I might care to contribute to his cost so I gladly offered my money box. I was rather disappointed to find that it didn't contain as much money (in copper coins) as I had expected but was very willing to part with it. I don't remember very much about Norman's infancy as there was a 7 year difference between us and my interests were chiefly out of doors with kindred spirits of my own age group.

Towards the summer of 1927 I became very ill and was found to have caught diphtheria. As there was a few month's-old baby in the house there was no question but that I had to go to the Isolation Hospital. Our house, or at least some of the rooms were fumigated with sulphur candles I believe, but I was not there to be certain of this. I was taken by ambulance to the “Fever Hospital” at Crow Wood, where I was put in a big ward with other children. At the time there was much diphtheria and scarlet fever about, both being dangerous and highly contagious diseases, and I had heard from schoolmates about the horrific treatments to be expected. In the event, I can only recall an injection in my bottom and having to drink mugs of some unpleasant tasting, brownish, porridge-like liquid from time to time. (I regarded this as the legendary “Brimstone and Treacle” and perhaps it was). I was much too ill to take much interest in anything else. I was in hospital for some weeks, Father and Mother coming to see me from time to time but as it was an isolation hospital we could only look at each other through the ward windows, no visitors being allowed inside the building.

When I was improving and could sit up and take an interest in things again, Father showed me a Hornby train catalogue through the window and sent it in with a note asking me to choose a train set from it. I settled on a goods train which he agreed to buy me when I returned home. After some convalescence at home, we went into Liverpool and Father bought me one of these train sets from the Hornby shop. I seem to remember that it was very expensive - perhaps as much as £1/8/6 (or in present day money 142.5 pence!). I was delighted with this train set which had a circular track, a clockwork tank engine with forward and reverse drive, an open wagon, petrol tank wagon, and a guard's van. Not content with a circular track, I saved up pocket money and bought extra straight length rails and ultimately a set of points and some buffer stops, which gave a more interesting layout. Mother didn't like me to play on the floor so I usually sat at the table whether I was playing with the train set, some Meccano or anything else. In summer I could set the track up in the back garden and operate it as a long, if serpentine, railway and run my goods train backwards and forwards. Down in Widnes, I had seen the railway crossings in Widnes Road with the rails set into the road surface, so I would bury the rails in the soil, only leaving enough exposed for the train to run on. On the whole however, I didn't find this train set as interesting as a Meccano set that I later acquired.

Before my brother Norman was old enough to join me, I slept by myself in the front bedroom which was lit by a gas-light on one wall. Later, when Norman shared the room (and the bed), we had a night-light or later, a small oil lamp, standing on the top of a cupboard in the corner of the room. When we had electricity installed in 1931, it was much better. When I lay in bed, I would listen to the trains on the Cheshire Lines Railway; they could be heard starting off from Farnworth Station and from time to time there was a goods train which would rattle along the line. This was a very pleasant sensation, when tucked up snugly in a warm bed on a cold night!

One evening, I remember that we were listening to play on the wireless and I was sent to bed before the end as it was past my bedtime. The play was about the mystery of the Mary Celeste, the brigantine that was found at sea but deserted, and took the form of a narration by a steward on a liner to some of the passengers. There were flashbacks to the possible events on the Mary Celeste which in this story was supposed to have been stalked and attacked by a monster octopus which plucked off the crew members one after the other. This story had a great impact on me and I was much too frightened to go upstairs to bed by myself in the dark when told to. Father had to chase me upstairs in a terrified state, and I was soon under the bedclothes where I felt safe.

I always felt quite safe under the bedclothes and would often read the stories in boy's papers by flashlight in this way although I was not supposed to. Once, I was reading one of these stories about a “Q-ship” during the War. These small, innocent-looking, coasters were fitted with a gun concealed under a mock deck-house, and when a German submarine surfaced to attack the vessel, a pretend “panic-crew” would hastily abandon ship and row away in a lifeboat. The submarine would then approach the coaster to sink it by gun-fire (much cheaper than torpedoes), and at a suitable moment, the Naval crew would uncover their gun and shell the submarine and sink it. As I was reaching an exciting part of this story, Father crept into the room and caught me. He took away the paper and burnt it, so I never found out how the story ended. Worse still, it was a comic that I had borrowed from another boy at school and I had a lot of explaining to do!

By 1926 we had a dog “Prince”, a small black mongrel with a white patch on his chest. I remember him as a quiet, friendly dog. He was killed by a bus in Albert Road near Woolworths, one day as we were shopping. Mother and I would go down to the Widnes shops on a Saturday afternoon and “Prince” came with us; we never had him on a lead as far as I can recall. On the east side of Albert Road was a Chinese laundry where a large and rather aggressive dog sat in the doorway. Prince was not an aggressive dog and had learned to avoid fights so he crossed the road some distance before reaching the laundry and walked along the other pavement before crossing back to us when well past the other dog. On his way back to us he was run down by a Corporation bus and the only thing we could do at the time was to move his body into the gutter. We were all very upset by this accident and it was some years before we had another dog.

By 1929 we had a pup, a smooth-haired white dog that we called “Mickey”. When he grew older, Mickey would sometimes sleep stretched out on the road and a bus driver would have to stop and shoo him out of the way as he didn't seem to be bothered by traffic. Eventually, he was in an accident with a motor-bike and sidecar in Lockett Road and was brought home badly bruised and shivering with shock. He was put in his bed under the sink in the kitchen and lay there for a day or two recuperating before he would venture out again. Once we had an irate cyclist at the door claiming to have been bitten by our dog. He would tend to chase cyclists, barking at the pedals. Mother brought the man in the house and treated a small scratch on his leg and repaired a tear in his trousers, sending him off somewhat pacified.

Father made a dog-kennel which was placed at the back of the house, to the left of the back door, and our dog was chained up at night to sleep in the kennel. Dogs have a tendency to howl in the night and Father would open the Lumber Room window above the kennel and try and discourage this. As I kept my collection of cigarette cards in this room, each pack being neatly tied up, Father when looking for the handiest missile to throw at the dog would find these bundles. The dog being suddenly presented with new playthings, would stop howling and start chewing. I lost a number of card sets in this manner!