Chapter 5: Work and War

I wanted to work in a chemistry laboratory although I had no clear idea what this would entail at that time. However, my desire was probably stimulated by an experience one weekend in the early 1930's when I had a memorable day out with my Father. He was a Plant Foreman at Marsh Works of I.C.I. and was often on shift work, sometimes working a full day at weekends. Marsh Works produced sulphuric acid in various strengths, and other sulphur-based chemicals including sodium sulphite, sodium thiosulphate (photographic “hypo”). It was thought that it might interest me to look round a chemical works on a quiet day and so it was decided that I would take our two dinners to have down there. I took a bus from Farnworth to Widnes Road and along Ditton Road round the turn to Marsh Works to the south. I needed to pass under the long railway viaduct leading from the railway bridge over the river. At the yard gates, the watchman who had been told of my coming let me in and rang Father to collect me. We walked through the works to the Foremen's office where he had his desk and worksite and I remember being impressed by the way the railway lines we crossed were sunk into the ground with only the rails showing.

After our meal I used a telephone for my first time, Father going off to some other point in the works and ringing me up! He then took me round the sulphuric acid plant and we climbed flights of stairs to see the burning of iron pyrites in furnaces on different floors. Rotating blades moved round each hearth stirring the burning pyrites which burnt with a bluish flame and emitted large amounts of sulphur dioxide into the atmosphere when the furnace doors were opened. A few men were charging the furnaces by hand with coarsely crushed pyrites. There were pyrite burners at ground level but my recollection is of a vertical series. The waste product was the residual iron oxide known as red ash which went to a tip.

Another visit was to the crystallising process for sodium thiosulphate where a hot concentrated solution of this salt flowed through a labyrinth of shallow channels depositing crystals as it cooled. The first crystals were quite small but at the end of the channels larger crystals were grown. The required sizes could be raked out at the appropriate part of the system. I was given some specimens to take home of course.

Our final visit was to the analytical laboratory which was not occupied at the weekend and we were able to browse round freely. Father had considerable experience in chemical sampling and testing, and showed me various apparatus used and got me to weigh something on a chemical balance as I had been learning at school. He gave me some test tubes and pieces of glass tubing and also one or two of the small evacuated bulbs used for sampling oleum - (fuming sulphuric acid) a very unpleasant and dangerous material to handle.

These souvenirs were tucked away in the small attaché case in which I had brought the dinners. When the time came to go home I got a bus to Farnworth Street and when I got home found that I had left my case on the bus! On enquiry at the bus garage we were told that the case had been handed in so I had a trip down to Moor Lane after the weekend to recover it. Quite an interesting day out for me and some equipment for chemical experiments as well, not to mention laying down possible thoughts for the future.

Consequently in 1936, I applied to I.C.I. (General Chemicals) at Central Laboratory, Widnes, and also to the I.C.I. Headquarters at Cunard Building, Liverpool, and in both cases was told that no vacancies were then available. Towards the end of September however, I was called for an interview at Cunard Building as a vacancy had arisen, and ventured into this impressive and overwhelming building. In my turn I was interviewed and questioned about my knowledge of chemistry and other subjects and remember being stuck on the Haber process for the synthetic production of ammonia.

There were other candidates, some being better qualified than myself so I was put on a waiting list for future reference. Becoming impatient after a few more weeks I wrote again to Central Laboratory on the advice of my father who had spoken to Dr. Leech who worked there; they were on friendly terms having worked together at various times in the past. This did the trick and I received a letter offering me a job as a Laboratory Assistant starting on Monday the 26th of October 1936 at 8.45 a.m. at a weekly wage of 16 shillings and 11 pence (about 85 pence). My hours of work were to be Monday to Friday 8.45-5.15 with one hour for lunch and Saturday mornings from 8.45 to 12 noon. I was informed that this was a non-staff appointment and consequently I would be on the factory payroll and as a 16 year old paid the standing wage in accordance with the stipulated rates for boys and youths, which after deductions left me with the princely sum of 15 shillings and 4 pence.

This offer was conditional on passing a medical examination and I was required to attend the Medical Room at Muspratt works on Friday the 23rd of October. I had no idea where this was, the complex of chemical works in Widnes stretching from Marsh Works on the west to Pilkington-Sullivan's on the east, a distance of nearly two miles of railway tracks and factory buildings. My father who had a good practical knowledge of the Widnes works was able to tell me where to go, so I got time off school and made my way through some dismal parts of Widnes, under a railway bridge and across lots of railway sidings and eventually found the offices and the medical room.

I joined another man in a grimy waiting room. He was Harry Fay, a plumber, who was having a routine test for lead. The medical examination and tests were carried out by Jack Parker who I later discovered was the chief first-aider/ambulanceman for the works. He listened to my heartbeat and tested a urine sample for sugar by boiling it in a tube over a bunsen burner and that was the extent of my medical examination. After a short wait he told me to report to Central Laboratory on Monday morning and that was that.

It was late in the afternoon by the time I had walked back to school to pass on the good news and as there had been a school lecture nearly everyone had gone home. The Headmaster, Mr Green, was entertaining the lecturer and staff in his study and wasn't at all pleased to be interrupted but came out into the corridor to hear my news. That was my last appearance as a pupil at the Wade Deacon Grammar School.

Over the weekend I took a walk down to Widnes to find out where the Central Laboratory was situated and I found this a help on Monday morning when, carrying a packet of sandwiches for my dinner, I waited near the entrance trying to decide which was the way in. At about twenty minutes to nine a crowd of young men rushed along from the train and I was swept inside with them, along some passages and ended up in a queue outside the chemical stores where the “signing in” book was kept. The stores hatch was open and everyone signed their names and the time in a book on the counter. At exactly 8.45 a.m. Whinyates, the officious storeman drew a thick red line across the page and anyone signing after this was LATE.

After signing-in the crowds dispersed leaving me standing there not knowing where to go; the storekeeper asked me if I had brought my cards but I didn't know what he was talking about. After some discussion he made a phone call and soon an office boy appeared and took me to the General Office, just inside the entrance door through which I had so recently been swept. After a short wait the office staff appeared, their timekeeping not being as strict as the laboratory staff, and Tom Seddon, the office manager, took command and made a few phone calls before the office boy took me along more corridors to a room where I met Mr C.I. Snow who was in charge of the Electrical Testing Laboratory as it was then called.

The rather small and narrow room served him as an office but it was also a laboratory, over half of it having test equipment along one long side. His desk was across the only window at the narrow end of the room which overlooked a narrow yard between two high brick-walled buildings. In the yard was a row of bicycle racks covered with a light roof - the laboratory bicycle shed. The room had been made by enclosing some of this yard and a few steps led upwards into the main building which contained the rest of the Electrical Laboratory. This was a large room divided into two parts by a central passageway with a high steel-mesh partition at either side.

The larger part next to the office/laboratory had teak benches with drawers and cupboards round three sides and in one corner a large steel-mesh high-voltage generating and test cage. A side door led out to the bicycle shed and the passageway through the room led to doors to the outside main yard and a large “semi-technical” building full of large machinery and chemical plant. The smaller part of the laboratory had a long window opening on to the main yard, fume cupboards, teak benches with cupboards, a sink, a large electrical oil-bath and a paper-condenser winding machine.

Claud Ivan Snow was a rather eccentric academic man but we got along all right and I was soon passed on to meet the other people in the laboratory; Mr J. Meek, a physicist who had a desk next to the high-voltage cage, Ironeth Thomas Pierce, another physicist with a heavily pock-marked face, with whom I started to work, and three laboratory assistants, Reg Forster, Joseph Timmins and Arthur Hescott. Arthur had joined I.C.I. during that year. Later in the year J. Meek left I.C.I. to work at Woolwich Arsenal and his place was taken by Vernon W. Rowlands, another physicist, fresh from Bangor University.

The first morning passed and dinner time arrived. We were allowed one hour from twelve to one but were forbidden to make drinks or eat food in the laboratory so when everyone disappeared at twelve I decided to go home for my dinner. I was quite unaware that there was a lunchroom in the nearby Gaskell's works at that time so I assumed that everyone made their own arrangements. It was a dull and damp day and having walked up Kingsway and reached Victoria Park I realised that I wouldn't have enough time to get home and back in the allowed hour so I sat in a park shelter and ate my sandwiches before walking back just in time for one o'clock. I found out about the works canteen for next day and that solved my dinner problems for that week. By the next Saturday my father had managed to buy me a second-hand bike from a workmate for thirty shillings (£1.50), so, early on Sunday morning we both set off for a ride so I could learn how to use it. Although I had never had a bike before, I soon got the knack of it and we rode along quiet roads to the Black Horse, along Lunts Heath Road and Derby Road and back home up Farnworth Street with only one slight mishap. This happened when, along Lunts Heath Road, a dog ran out in front of me; instead of using my brakes I jumped off the bike, which was not a good thing to do at the speed I was travelling.

After this gentle introduction to cycling I started riding to work on the Monday morning, coming home for a hot dinner at midday each day and again in the evening. In the 1920's and 1930's, the law required all bicycles to be fitted with lamps at night from the official “Lighting-up” time and during the hours of darkness. My Father, who cycled to work at Marsh Works in Widnes, used an acetylene lamp which required a great deal of maintenance. The acetylene was produced as required by the reaction between calcium carbide and water, the carbide being sold in small lumps in liver-lidded tins. The lamps were made of brass, the carbide container occupying the lowest section with a container of water above this. A knob at the top controlled the drip of water to the carbide and this gas was then fed through a filter to a ceramic burner backed by a metal reflector. A great deal of work had to be done to clean out the carbide container and keep the jet of the burner unblocked. It was much easier when battery-powered bicycle lamps came into general use, although there was the need to buy replacement batteries fairly often. Coming home in the evenings in the autumn and winter months I had a battery-powered lamp and used it until the bulb glow became too dim for use like most of my friends at that time. It was common practice to warm an old failing battery in a laboratory oven as 5 o'clock approached and this had the effect of giving a much brighter light for some time until the battery cooled. The Law was rather strict on riding a bike without lights after lighting-up time although a red reflector mounted on the rear mudguard was accepted. (At the outbreak of war, bicycle lamps had to be fitted with a metal visor so that no light was directed upwards to attract the attention of the enemy. This made it quite difficult to see where you were going at times). Frank Smith's older brother Jack was once stopped by a policeman while he was riding a bike with no light after dark. He demanded his name and when he replied “Jack Smith”, told him not to be silly as he had heard that trick before.

On Saturday mornings we worked until twelve o'clock, much of this time being taken up in cleaning and repairs to equipment. The benches had to be cleaned, the most heavily used one being wiped over with shellac varnish which we made ourselves. Stocks of solvents were replenished as we used a lot of benzene, trichloroethylene, acetone and alcohols. Although it was forbidden to make drinks in the laboratories, a stores labourer (Jimmy) brought round tea in 250 ml tall pyrex beakers during the morning and afternoon at a cost of a halfpenny a glass.

The Electrical Testing Laboratory had only been started about 1933, mainly for the routine testing of “Seekay” waxes, a range of chlorinated naphthalenes which were used as impregnants for wire-wound electrical components and paper capacitors. The complicated measuring equipment we used had been built in the lab and required great skill and patience to operate successfully. Some of the labels and scales on it had been made on aluminium strips by a coin-operated embossing machine on a station platform, and some of the test sets used radio batteries and lead-acid accumulators which needed constant attention. Other work involved electrical measurements on insulating varnishes for cloth and paper, early forms of plastic including polymethylmethacrylate (Persex), routine high-voltage breakdown tests on transformer oils from Marsh and Kemet works, and extreme-pressure lubricant research.

I was involved in the start of the lubricant testing, making solutions of chlorinated waxes in mineral oils and measuring the wear on metal test pieces in these solutions in various machines. J. Meek left us later in the year and after a collection in our lab we raised enough money to buy him a small filing box and cards; he came round and thanked us individually and seemed quite pleased with his small present. When V.W. Rowlands started in his place I worked with him at times on the transformer oil testing and found him a pleasant and friendly character. He lodged at Hough Green and kept a horse on which he was said to have ridden to work one day before being told by the management to take it home. He was also said to ride his bike in the rain holding up an umbrella. He advised me to smoke small cigars as he did in preference to cigarettes as you could let them go out and relight them at intervals; this saved money as one would last all day!

Towards the end of the year, a large and powerful oil-testing machine, the Timken Machine was installed just inside the adjoining semi-technical building and I was fully involved in operating this for a long time. It was tedious, hard and messily oily work which I didn't enjoy at all!

The extant narrative does not detail his further progress as a Laboratory Assistant beyond this point. It resumes to describe experiences in the Home Guard between 1940 and 1944, including guarding for a time the Central Lab where he continued his daytime employment as a result of being deemed to be in a “reserved occupation” at that time exempt from call-up for Army service.

When the War broke out everyone expected immediate air raids and much action but for about six months very little seemed to happen and there was a general fading of interest. This period became known as the “Phoney War”. Everything changed in Spring 1940, when the German Blitzkrieg started and their armies began to overrun Europe. In May 1940, the Allied Forces in Europe were under heavy pressure from the Germans, and Belgium and the Netherlands, both nominally neutral, were invaded and forced to surrender by the 28th of May. The German Blitzkrieg was also directed at France, by-passing the western end of the defensive Maginot Line (which only ran as far as the Belgium frontier). From May 10th until May 31st the Allied Forces were pushed back on to the French coast around Dunkirk, and by June 4th the evacuation by sea of the British Expeditionary Force together with many French and Belgian troops was completed. France surrendered on the 22nd of June. On the 14th of May, during the dark days when the German army was pushing across France, Anthony Eden made a radio broadcast calling for men between the ages of 17 and 65 and not in military service to come forward to form what he called the Local Defence Volunteers (L.D.V.). This force was meant for local service only, training to be carried out in spare time after work and at weekends, and would only be used in the event of invasion or other emergency. This service was to be unpaid.

On the way home from work the next day, I called at the Victoria Road police station and joined the queue to enrol as a volunteer. I was eventually told to report to the Barracks in Peelhouse Lane on Friday, the 7th of June for training and in due course was issued with a denim jacket and trousers, boots and leather gaiters, an armband bearing the letters LDV, a sidecap and other items. Later, we were to be issued with normal army battledress, a greatcoat, a haversack, a service respirator etc. The denim uniforms were very ill-fitting and the subject of much ridicule, the collars in particular were very large and some people could pull their tunics over their heads. The boots were hobnailed and one could produce a shower of sparks by skidding on a hard surface! Our status was defined by a khaki armband printed with LDV in black.

The title LDV was subject to some criticism in official circles and the organisation was re-named the Home Guard by Churchill in July 1940 when we were issued with fresh armbands printed with this title. Our unit was officially the 80th South Lancs Battalion and our cap-badge was that of the South Lancs Regiment. Strict Regular Army discipline was not possible with such a mixed volunteer unit although there was a lot of genuine enthusiasm and keenness in those early days and everyone wanted to play their part. Our duties were vague - perhaps as guards or observers of airborne invasion - but we wanted to play an offensive role against an invading enemy even though the authorities were not keen on arming “civilians”. Churchill, however, was very enthusiastic and approved the manufacture and issue of a number of improvised weapons as well as traditional ones.

One of our earliest duties was to clean thick grease off a number of rifles of First World War vintage which had been imported from America where they had been in store since that time. As I recall, they were 1917 0.300 Springfield rifles of American origin but in very good serviceable condition. There was no suggestion of drilling with broomsticks as some units were said to have done, neither did we come across the improvised pikes that Churchill had put into production in some parts of the country. We used clips of dummy rounds for practice but, I should say at this point that, as far as I can remember, we were only issued with live ammunition when on the firing ranges. Of course we always had our bayonets and scabbards carried on our belts in leather frogs. We were issued with these long bayonets and were allowed to take them home as part of our uniform; some people, myself included, sometimes took a rifle home to practice with although this was quite illegal. (After the War, I found that I still had my Home Guard bayonet and it is now bricked up in the old fireplace in the cellar!)

In some parts of the country, live ammunition must have been issued, as during the early days there were a number of fatalities when over-enthusiastic volunteers shot people who failed to stop at road blocks and even fired at R.A.F. airmen coming down by parachute. There were many rumours of Fifth-Columnists and saboteurs operating in the country disguised as nuns, policemen and other civilians and this made everyone very suspicious of any strangers in the area, so perhaps it was as well that we had no live ammunition! Even policemen were stopped for identity card checks! There was a certain amount of over-officious zeal and self-importance among some volunteers and a story was told of one civilian being stopped twenty times on a journey of eight miles to have his identity card checked repeatedly.

Our training took place at the Barracks every eighth night between 7 and 9 pm when we were on duty as an “inlying piquet”, sleeping on wooden double-tier bunks covered with chicken wire and using straw-filled palliasses. Our group contained a range of volunteers, some being rather irresponsible youths who, until they were sorted out, larked about in the dark after we had settled for the night. Between 9 to 12 on Sunday mornings we paraded for “Operations”, travelling in a single-decker Corporation bus to various sites to observe demonstrations of weapons or take part in exercises. One of our first operations was to a site on the south side of Ditton Road towards the station, where we had to dig trenches along the western edge of an old tip-heap of chemical waste. This was designed to be a defensive position against an attack coming from the direction of Ditton station. To the best of my knowledge this site was never used and perhaps it was just as well as it was very poorly sited and gave quite inadequate protection. Looking back, I think that we would have had no chance against the battle-hardened German Army despite our enthusiasm. The formation of local defence units was a great morale booster at a time of national crisis and that was the important factor.

Another early outing was to the quarry on Pex Hill where we were given a demonstration of rifle firing by Sergeant Instructor Wilkinson, an old regular soldier who was attached to our unit for training purposes. The target was a thick steel plate propped against one wall of the quarry and he fired several rounds at it across the length of the quarry, causing a number of deep dents but no penetration. This was the first time I had seen an army rifle fired against a target. We fired our first rifle shots at ranges on Widnes Marshes in the Moss Bank area, to the north of the St.Helen's canal. These ranges were on a large expanse of waste ground and had a number of targets set up at various distances. A few of us were so successful at this that we were classed as “snipers” and given special instructions in musketry. The sights on these old rifles were so easy to use (they had a ring backsight) that I found I could get fair results. Later, in the Army, using the 0.303 SMLE (short-muzzle Lee Enfield) rifles with plain sights, I was not nearly so good a shot. There was also a miniature rifle range at the barracks for 0.22 rifles which we used at times, firing on small card targets and hoping for a close grouping with 5 shots.

On another exercise on the Marsh we were instructed in the use of the Northover Projector, a primitive and most dangerous device (including risk to the operator). Designed by Major H. Northover, this weapon consisted of a steel tube mounted on a cast-iron tripod, which was used to fire an SIP (Self Igniting Phosphorus) grenade (a half-pint, crown-cork, glass bottle filled with a mixture of a flammable liquid and yellow phosphorus) some distance on a low trajectory. The bottle, backed by a felt wad and a propellant charge set off by a cap, was meant to be fired through the tube at an enemy armoured vehicle with the object of setting it on fire. It was a simple line-of-sight weapon, not accurate over about 150 yards and with a number of drawbacks and risk to the three man team who operated it. It was very important to check that the foresight on the barrel was not screwed down too far or else the bottle would catch on it, smash, and explode in the barrel and cover everything with burning petrol and phosphorus! We all had a go at this on the marsh range. I don't remember this device ever appearing again after this solitary trial and I never heard of it again.

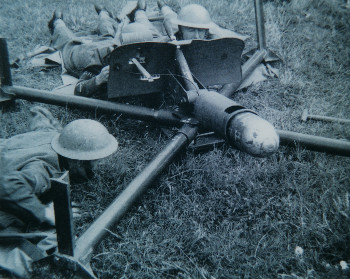

Towards the end of 1941, we were given another interesting demonstration one Sunday morning at the Clayhole, a wide and deep, flooded pit in fields to the north-west of Derby Road. We were treated to several firings of the Blacker Bombard (later known as the Spigot Mortar). Designed by Lt.Col. L.V.S. Blacker, a T.A. artillery officer, this was a sturdy device which fired a hollow-charge projectile designed to penetrate tank armour. It was fired by a spring-loaded steel rod which, when released, struck a charge on the end of the projectile and propelled it over a fairly short range. It was of poor accuracy, had a heavy recoil and weighed about 3 cwts; it could fire either a 20 lb anti-tank or 14 lb anti-personnel bomb. The projectiles that we saw fired were inert, with the explosive charge removed and replaced with sawdust. They were fired over several hundred yards across the large pit at a makeshift target and I was not terribly impressed at their accuracy. As with the Northover Projector, I don't remember seeing this weapon again after this demonstration.

During these times when the German invasion seemed imminent, the weekly magazine Picture Post had a number of articles written by Tom Wintringham, a notorious left-winger who was a veteran of the Spanish Civil War. He had been the Commander of the British Battalion in the International Brigade and became the military correspondent for Picture Post. His subject was guerrilla tactics and he described the making of Molotov cocktails, ambush weapons such as the “Flame Fougasse”, and various other improvised weapons and defences based on his experiences. These were discussed but our methods were more orthodox and I don't remember any of his ideas being carried out in our unit. Most of our training was in use of the rifle and bayonet together with simple drills, and as the officers were all volunteers like ourselves the only professional link was with Sergeant Wilkinson, rather a rough and ready character and not the best instructor we could have had! Practice in aiming a rifle was carried out by two people lying prone on the floor, one aiming his rifle at a disc, with a small central hole, held by the other, who could look through this central hole to check on the steadiness of aim as the rifle trigger was pressed. It was important to check that the rifle was not loaded!

On some occasions we took part in mobile patrols around Farnworth, especially during air raids and once had to take cover at the roadside along Norland's Lane when shell fragments fell around us from anti-aircraft fire in the vicinity. We were on our way to Pex Hill where there was a sandbagged machine gun post manned by Regulars, and when we heard the whistle of falling bombs in the vicinity, we all piled in behind the sandbags to the great inconvenience of the occupant. At times, the Germans dropped empty parachutes to cause alarm and rumour and we were called out one evening after an air raid and taken by bus to a point in the Tarbock area where we had to search a wood after a report of a parachute coming down. After a long and fruitless search in the dark we returned to the Barracks and it was later rumoured that a parachute had been found attached to a dummy figure.

One regular duty was to man a road-block across Birchfield Road at the Black Horse pub. The road was narrowed to a single carriageway and three of us on duty had to stop everyone passing and check identity cards; as only the odd cyclist and pedestrian used the road during the night it was very boring. What we were to do with any unidentified wanderer was never stated!

The platoon sergeant was Reg Platt from Platt's Widnes Foundry and during the long hours of the night we had many an interesting talk about astronomy (he had made his own telescope) and other topics. During the black-out there were no lights anywhere and with a clear sky the stars were more visible than they have ever been since. We must have had somewhere to rest between our spells of duty but I have no recollection where this was. Some of the youths in the platoon would raid an apple orchard at a farm on the west side of the road while they were not supervised.

Over the weekend of Saturday / Sunday, the 7th / 8th of September, 1940 there was an invasion scare when troops in Eastern and Southern Command were brought to full alert as favourable tides were thought to make an invasion attempt likely. The alert was issued by General Headquarters Home Forces using the formal code word designated for an actual invasion, “Cromwell”, while informing other Commands that this was merely a precautionary move. Unfortunately in certain areas, the Home Guard was not let in on the secret! The result was not quite Dad's Army's finest hour, but certainly one of its most valiant if also most chaotic ones. In Cornwall, the Vicar of St. Ives, seeing the local fishing fleet returning from the west instead, as was usual, from the east, mistook it for an enemy force and ordered the church bells to be rung, the accepted signal to announce the enemy had landed. The bells acted like the beacons of 1588 proclaiming the approach of the Spanish Armada. By late evening throughout large sections of the country, from Cornwall to the Western Isles, the skies were being scanned for parachutists, while countless roads echoed to the sound of the Home Guard challenge “Who Goes There?”, with occasional rifleshots when challenged parties failed to stop.

The first we knew of any of this was when one of our platoon members came to our house on the Sunday morning to call us out in order to man an observation post at the old smithy at Upton Rocks. (By now, Father too had joined the Home Guard). We were told to bring rations for 24 hours but settled for some sandwiches and a thermos of tea as we were not far from home and could easily slip off home for some more. At the smithy we met up with a number of other local Home Guards and a look-out rota was drawn up. One of the more “well-built” members of the platoon complained that his rations for 24 hours were more than he could carry!

The old smithy at Upton Rocks was a substantial sandstone building which had been derelict for a long time but the upstairs floors were sound and we could look out through the broken windows over the fields to the west. The ground floor which had been the actual smithy still had a forge and a large pair of leather bellows which could be pumped. There were two rooms upstairs, the more northerly one having a step down into it from the passageway. Here, some joker had torn a long strip of paper off the ceiling so that when the door was opened and you stepped down into the room, a long white shape suddenly dropped down on you. Altogether, the place was very eerie during the night hours! After a long and tedious watch during which nothing happened we were informed by runner that we could stand down. It was very much later that we heard the full story of the invasion scare which had provoked this exercise.

By the end of 1940 we had been issued with battledress uniforms and various new weapons appeared in small numbers, for example, the Browning automatic rifle and the Thompson sub-machine gun and we were shown demonstrations of these. I don't remember firing them myself. The beginning of 1941 saw an increase in air raids culminating in the Liverpool blitz in May and from our garden at Farnworth we could see aircraft in the evening sky towards the west and the bursts of anti-aircraft fire near them. In March 1941 a Heinkel bomber was shot down by a Hurricane fighter plane and crashed near the I.C.I. Recreation Club in Liverpool Road, the bodies of the crew being later buried in the Birchfield Road cemetery. On the Sunday after this action we were involved with an exercise with a unit of the Regular Army who were supposed to be testing the Widnes defences. Our platoon was to hold a position at the club house of Naughton Park rugby ground in Lowerhouse Lane and for several hours on the Sunday morning we kept a look out from the doorway on the approach from the north. There were very few people about but we did meet a boy who had come from the German crash site with some souvenir fragments. Towards the end of the morning we observed a solitary soldier walking down the road on our side, and in our way we “ambushed” him as he passed by. His reply was that he represented a platoon with automatic weapons and we were to consider ourselves wiped out!

Once, a report came in of a suspicious character lurking on the fields north of Liverpool Road near the golf club and a small party was sent to investigate under the command of P.S.I. Wilkinson. They came across a man who ran away when challenged so the sergeant fired one round at him hitting him in “the left buttock” as was stated in his report. He proved to be an Army deserter on the run according to what we were told. This was the only case I heard of about anyone being wounded as a result of Home Guard activity in our area.

At a somewhat later date, the Widnes Home Guard took on the duty of mounting an overnight guard on the Old Bridge, the railway bridge over the river Mersey. Besides the railway lines, this bridge has a walkway which was open to cyclists and pedestrians at that time and was the only way to cross the river after the transporter bridge had shut down for the night. This walkway was only closed after the new road bridge was opened in the 1960's. On the Widnes side was a small ticket office to shelter the man who collected the toll of one penny for each person using the bridge. We were involved in this bridge guard duty on a regular basis, travelling from the Barracks to West Bank by bus in the evening and based in West Bank school between our respective turns of duty. We took turns at bridge watches of two hours each with the object of preventing sabotage and if the weather was bad we could shelter in a sentry box at the Runcom side of the river. I don't recall that we used this sentry box much but it was occasionally occupied by a sailor and his girl by our special permission. Very few people came across the bridge at night time and I can remember that patrolling back and forth across it during the early hours was most a most lonely and dreary business, especially while listening to the dismal sound of the hours being struck on the clock at All Saints Church in Runcom.

It must have been during 1942 that I transferred to the so-called Intelligence Section at the Barracks. This was in charge of an officer, Dr. Wiggins, from I.C.I. Marsh Works and I think that Father had a hand in this move. The section was made up of a small number of volunteers, none of whom I had met before, and our office was in a room to the right of the entrance to the drill hall with maps and diagrams on the walls and a big central table. We had instruction in aircraft recognition, ranks and uniforms and organisation of the German Forces and also spent much time in assembling a large-scale map of the Widnes area on one wall of the room. This involved the tracing of many small sheets of large-scale maps (25 inches to the mile) the resulting tracings then being pieced together and mounted on a wall of our office; this was a difficult matter, as I recall, as the sheet edges did not always match up and some judicious adjustments were required. Another of our duties was to visit and measure up various bridges, including the Old Bridge, to provide information for possible demolition in case of need. This work seemed to be rather late and unnecessary by 1942 but I must say that it was more interesting than patrolling the Old Bridge during the night! By this time it was considered that invasion was not very likely and there was a decline in the earlier enthusiasm although we still carried on with our training. I seem to remember that the Sunday morning parades were discontinued at this time as far as I was concerned.

In January 1943 I married and moved to Frodsham and as this would require much travelling to keep up my parades at the Barracks, I arranged a transfer to the Home Guard section at Central Lab where I was working. This was much more convenient as I could stay on after work instead of having to travel to the Barracks every eighth night. At Central Lab the duties were purely nominal, and we were associated with the nightly laboratory fire-watching teams. We inspected, cleaned and oiled the few rifles in the armoury if necessary but had no parades or other duties as far as I can recall. We only had to turn out in the event of an air-raid warning, a rare event at this time. There were only a few of us on duty on any one night and we passed the time playing snooker on a miniature snooker table and in conversation with the men from the workshops who made up the fire-watching team. I also made a one-valve short-wave radio in the lab on one occasion and succeeded in getting a signal from an American station! I slept on a camp bed in our office on the first floor, rising before the cleaners came in the morning so I could put the bed and blankets back into store. I cannot recommend sleeping in a stuffy office in the polluted atmosphere of a chemical works as I always woke up feeling the worse for wear. I would wash and shave and then prepare my breakfast in Lab 47, making toast with a Bunsen Burner and wire gauze, and poaching an egg in a porcelain evaporating dish and making tea in a Pyrex beaker. The laboratory was screened off from the adjacent passageway and I would hear the cleaning ladies comment on the aroma of fresh toast as they passed along to do their work.

My service in the Home Guard came to an end when I was called up in March 1944 and moved to a Primary Training Unit at Brancepath, County Durham. After I left, the role of the Home Guard which was becoming increasingly irrelevant to the war effort was questioned, and later in 1944 the organisation was ordered to “Stand down”. Looking back, the chief function of the Home Guard was more as a morale booster during a time of national emergency and it certainly carried out this role. Perhaps it was as well that it was not put to the test in combat with an experienced invading army.